In the 1980s, the HIV/AIDS epidemic in New York City became more widespread than anywhere else in the U.S. Due to the city’s large gay community, local doctors saw a huge number of cases. This led to fear and panic, but at the same time, community activists and politicians did a lot to fight the epidemic and change people’s attitudes toward the new disease. Improvements in therapy and prevention helped stabilize the situation. Read more on i-new-york.

Where It All Began

In 1969, a teenager in St. Louis died of a disease that doctors couldn’t diagnose. Almost two decades later, molecular biologists in New Orleans discovered the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in samples of his tissue.

Individual cases of AIDS were recorded before 1970. According to modern research, up to 300,000 people may have already been HIV-positive during that period. However, very little was known about the disease. Diagnosis was difficult, and treatment was out of the question.

In late 1980, a schoolteacher in New York died of AIDS. He had gone to doctors in the fall of 1979 complaining of hard lymph nodes and a strange purple rash on his skin. After an examination, he was diagnosed with Kaposi’s sarcoma. Doctors were surprised by the case because this type of cancer was mostly found in elderly men of Mediterranean descent. The teacher was just over 30. By the end of the next year, he had developed an unusual lung infection and soon died. The cause of death was AIDS.

The HIV/AIDS Epidemic

Throughout 1981, more and more strange cases and mysterious diseases that often led to the rapid death of patients began to be recorded in New York City. For example, there were reports of gay men with pneumonia caused by Pneumocystis carinii. This rare form of the disease was exclusively found in patients with severely suppressed immune systems. Additionally, Kaposi’s sarcoma was becoming more common among gay men in New York.

Local newspapers started to report on it. In May 1981, journalist Lawrence Mass was the first to write about the new mysterious epidemic in the publication “New York Native.” However, under the headline, he wrote that rumors of a terrible disease were largely unfounded. Officials at the time still denied information about the epidemic, although the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention were actively collecting information on every atypical case.

The new disease was then described as a “gay-related immunodeficiency” or “gay cancer.” This media reporting mistakenly created a link between homosexuality and the new disease.

By the end of the year, 337 cases of severe immunodeficiency were reported in the U.S., mostly among adult men. Some of the infected were also teenagers. More than 100 of the sick did not survive the year.

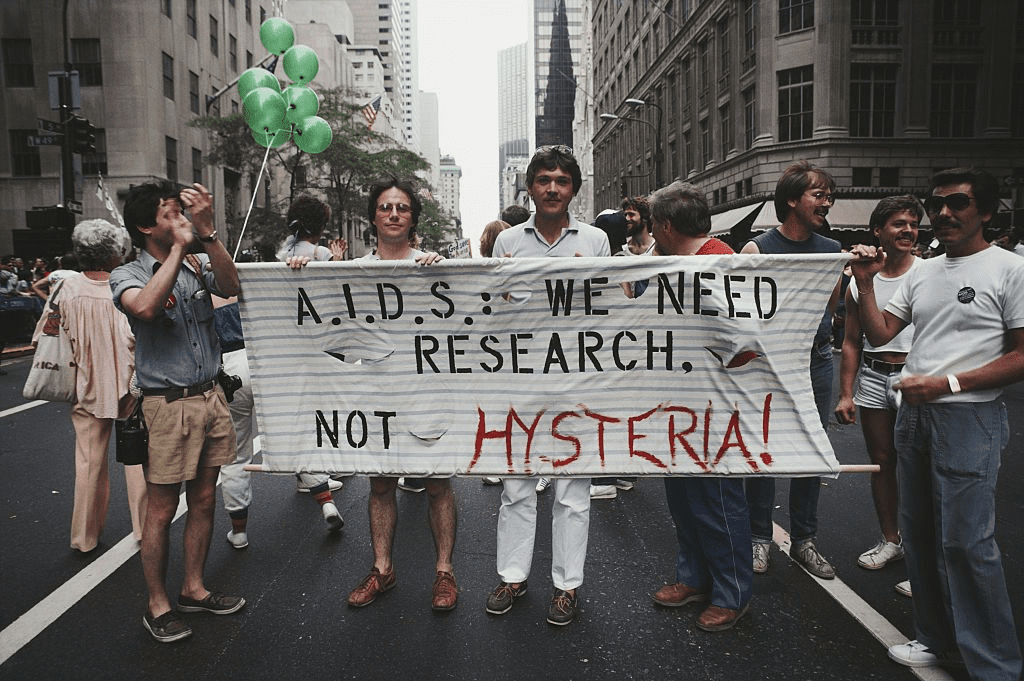

It was no longer possible to ignore the new disease, especially in New York, where the most cases were recorded. This caused panic and the spread of rumors among the population, which had a negative impact on the city as a whole.

Larry Kramer, a famous writer and producer, held a meeting with representatives of the gay community to discuss the epidemic. Kramer invited Dr. Alvin Friedman-Kien and asked the participants to raise funds to support his research. This was the first private money in the U.S. raised to fight the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

The Development of the Epidemic

In 1982, the Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC) organization was founded in New York. Its goal was to organize the fight against AIDS among the city’s residents. One of the volunteers set up a hotline to provide information and advice about the new disease. On its first day, it received more than 100 calls.

At this time, the new disease began to be found not only among men, especially gay men, but also in people with hemophilia, women, and infants, as well as in patients who had received blood transfusions. This led to the hypothesis that the infectious agent was transmitted through blood and sexual contact.

Newspapers were now openly writing about the new epidemic, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention introduced the term “Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome” (AIDS). The disease now had a name, and the main risk factors for infection were identified:

- Male homosexuality

- Intravenous drug use

- Haitian origin

- Hemophilia

In 1984, Dr. Robert Gallo and his colleagues at the National Cancer Institute found the cause of AIDS. The specific retrovirus was designated as “HTLV-III.” A diagnostic blood test was developed to detect the virus, and the search for a vaccine to treat and prevent it began.

The search for a specific vaccine remains one of the challenges for humanity. However, over the past decades, drugs have been developed to help people with HIV and AIDS. The first one, for treating HIV, was called “AZT” and later became known as zidovudine. It was manufactured by Burroughs Wellcome. Clinical trials were conducted in New York and other U.S. cities. When it was launched, it was the most expensive drug in the world. The cost of a year of treatment was $10,000.

The first positive results contributed to the further development of this field. It gave patients hope for a full life, and most importantly, the scale of the epidemic was slowly being brought under control.

Education and HIV/AIDS Prevention

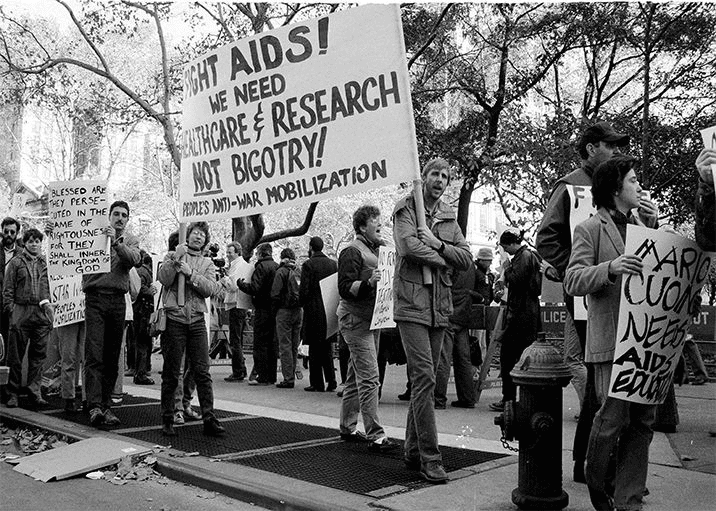

As early as the 1980s, public and private institutions in New York began creating educational programs for the public. The need for them became obvious after the first waves of fear and panic that divided society. Informational meetings and public forums were held, special literature and hotlines for consultations appeared, and a powerful information and education campaign began.

The “HTLV-III” hotline operated from 1982. It offered consultations for people with AIDS. Its employees met with representatives from the New York State AIDS Institute, the New York Blood Center, and the Hemophilia Foundation to coordinate their efforts. After a phone consultation, it became possible to get a referral for testing and further treatment.

In 1985, Gay Men’s Health Crisis developed a comprehensive education program for high-risk groups for HIV infection. Offices were opened in the Bronx and Brooklyn for educational activities.

Since then, politicians and community activists have dedicated a lot of time to HIV/AIDS prevention in New York. This helped curb the epidemic by the early 2000s and has kept its scale in check ever since.

In 2014, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo announced the implementation of enhanced HIV screening and testing, the promotion of prevention, and improved clinical care for HIV-positive individuals. According to the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, the number of new cases is decreasing every year. This proves the effectiveness of the measures implemented to overcome this epidemic.