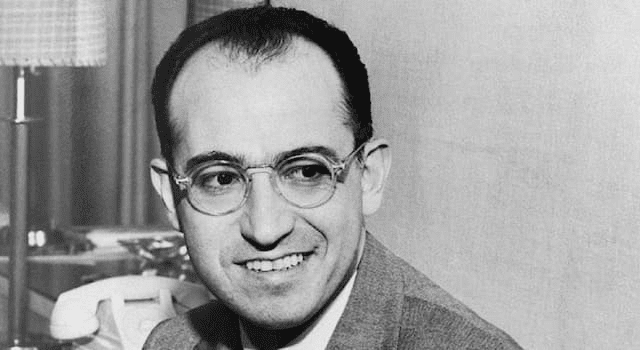

Until the mid-20th century, polio was one of the most terrifying infectious diseases on the planet. Hundreds of thousands of children died from it, and many who contracted it were left paralyzed for life. Scientists had long sought a way to conquer polio, and it was a New Yorker, Jonas Salk, who succeeded. He developed the world’s first polio vaccine and had such faith in its effectiveness that he inoculated himself and his three children first. Millions of children owe their lives and health to Jonas Salk. Read on i-new-york to learn more about the life of this groundbreaking virologist.

Jonas Salk’s Education and Family

Jonas Salk was born in New York City on October 28, 1914. His parents, of Jewish heritage, had immigrated to the U.S. from Poland. The family lived in East Harlem, and Jonas had two brothers. His father worked as a tailor and did everything he could to ensure his children had the opportunity to get a good education.

Jonas attended City College of New York, where he earned his bachelor’s degree. During this time, he became interested in medicine and decided to become a doctor. The young man wasn’t seeking financial gain; instead, he was drawn to scientific research and enrolled in New York University School of Medicine.

In 1939, Jonas Salk received his M.D. and began a two-year internship. After completing it, he left medical practice to dedicate his life to scientific inquiry.

As for his personal life, after university, Jonas married Donna Lindsay, the daughter of a New York dentist. The couple had three sons, and their marriage lasted nearly thirty years. Salk later married French artist Françoise Gilot.

Virology Research and the Triumph Over Polio

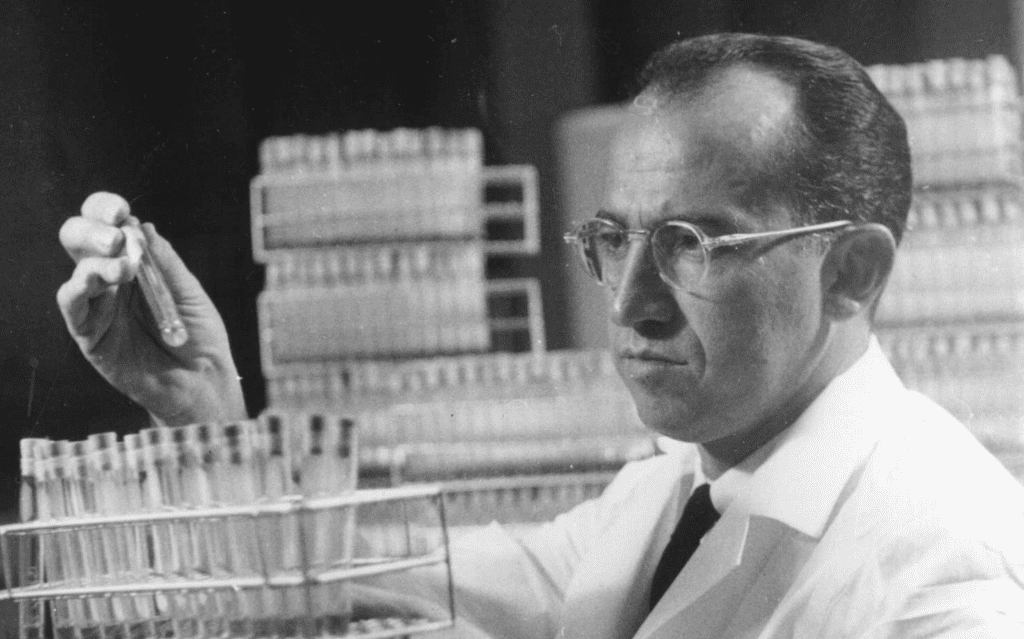

In 1941, Jonas Salk began an in-depth study of viruses. This field of medicine was largely unexplored at the time, and viral epidemics and pandemics left humanity helpless. In fact, Salk himself introduced the term “virology.” After two years of intensive work, he developed an effective influenza vaccine. By the end of World War II, it was being used by armies not only in the U.S. but also in Allied countries.

Jonas Salk’s greatest scientific achievement was his victory over polio. At that time, the disease affected hundreds of thousands of children annually, with most not surviving. Prominent figures like writer Arthur C. Clarke, film director Francis Coppola, violinist Itzhak Perlman, and U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt all suffered lifelong consequences from childhood polio. In 1948, the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis allocated funds for polio virus research.

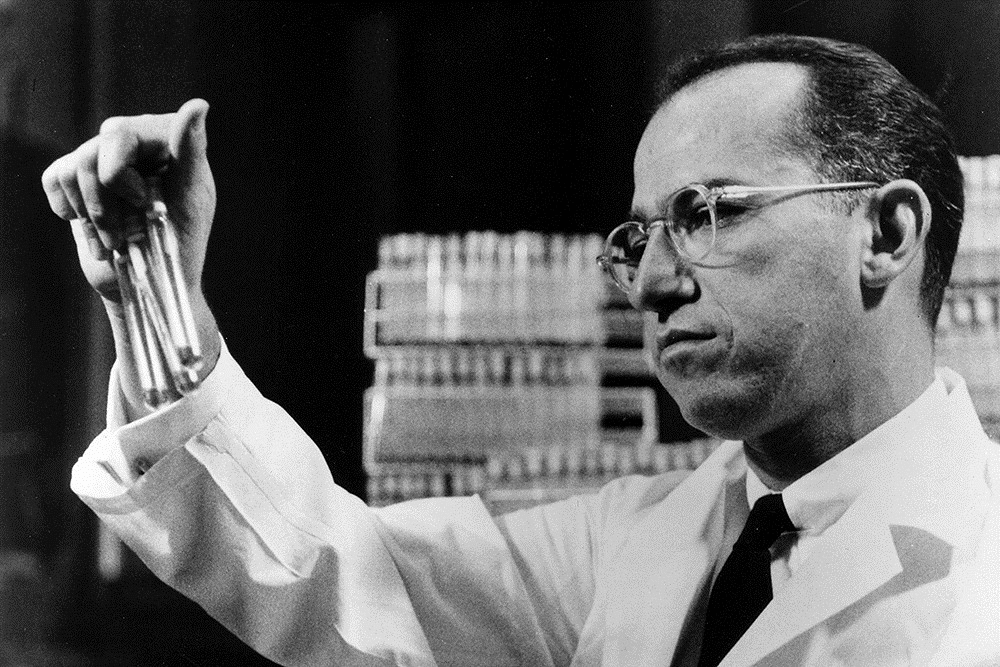

Jonas Salk joined this project. He was determined not only to study and describe the insidious virus but also to create a vaccine to prevent the disease. The scientist successfully isolated the virus, inactivated it using formalin, and created a vaccine based on the resulting material. The idea was that inactivated viruses could stimulate the production of the body’s own antibodies without causing the disease itself.

Salk was confident in the success of his creation. After laboratory trials, he inoculated himself and his own children with the new vaccine. Rigorous research continued for three years, and finally, on April 12, 1955, the polio vaccine was presented to the world. According to its inventor, two vaccinations would lead to protective antibodies in 90% of cases. If administered three times, antibodies would be present in 99% of patients.

Pharmaceutical companies agreed to produce it, and Salk insisted that all vaccines also be tested for safety in his own lab. He felt personally responsible for the drug’s quality.

Mass Polio Vaccination

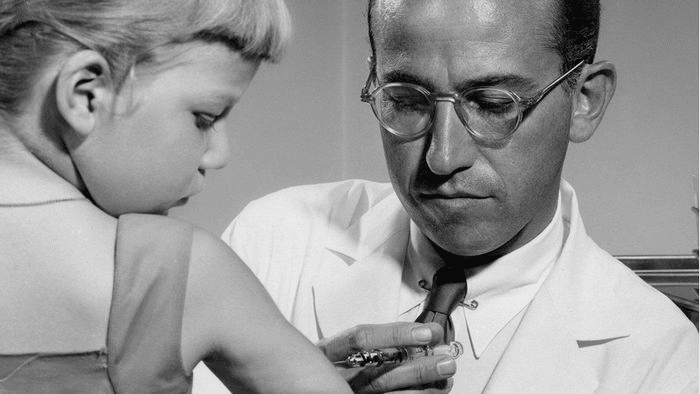

The first mass vaccination campaign, as part of clinical trials, took place in the spring of 1954. It involved 750,000 children, with an additional half-million vaccinated voluntarily. When the vaccine’s effectiveness was confirmed a year later, it was launched into mass production and widespread use.

The mass polio vaccination campaign for children in the U.S. began in 1956. Five years later, the incidence rate had dropped by an astonishing 96%. This remarkable result became a sensation for the global community. Jonas Salk became a hero who saved the world from the polio epidemic.

From then on, the vaccine began to be used in European countries. By 1969, approximately half of all children in the U.S. had been vaccinated, and polio incidence continued to decline. For his groundbreaking work, Jonas Salk was awarded:

- the Lasker Award (often called America’s Nobel Prize)

- the Koch Prize

- the Presidential Medal of Freedom

- the Congressional Gold Medal

- the French Legion of Honor, and many other accolades.

The Hebrew University of Jerusalem invited the scientist to be an honorary professor. From 1951 to 1963, Jonas Salk served as an advisor on viral diseases to the WHO. But the greatest reward for the scientist was the opportunity to work at the University of California. In 1963, a dedicated institute was created there, which Salk went on to lead.

It’s worth noting that the inventor did not patent his discovery. Salk could have become a millionaire, yet he and his family lived on an annual salary of $25,000. He wasn’t seeking profit from the vaccine; instead, he did everything possible to maximize its global distribution.

The widespread use of the vaccine among infection-prone children from 1956 to 1961 reduced incidence by 96%. Although it was later replaced by the more advanced Sabin vaccine, this did not diminish the importance of Salk’s achievement. In 1991, the WHO declared that polio had been defeated in European countries and the U.S. Incidence also decreased in Africa and Asia thanks to mass vaccination campaigns.

Further Research and the End of the Scientist’s Life

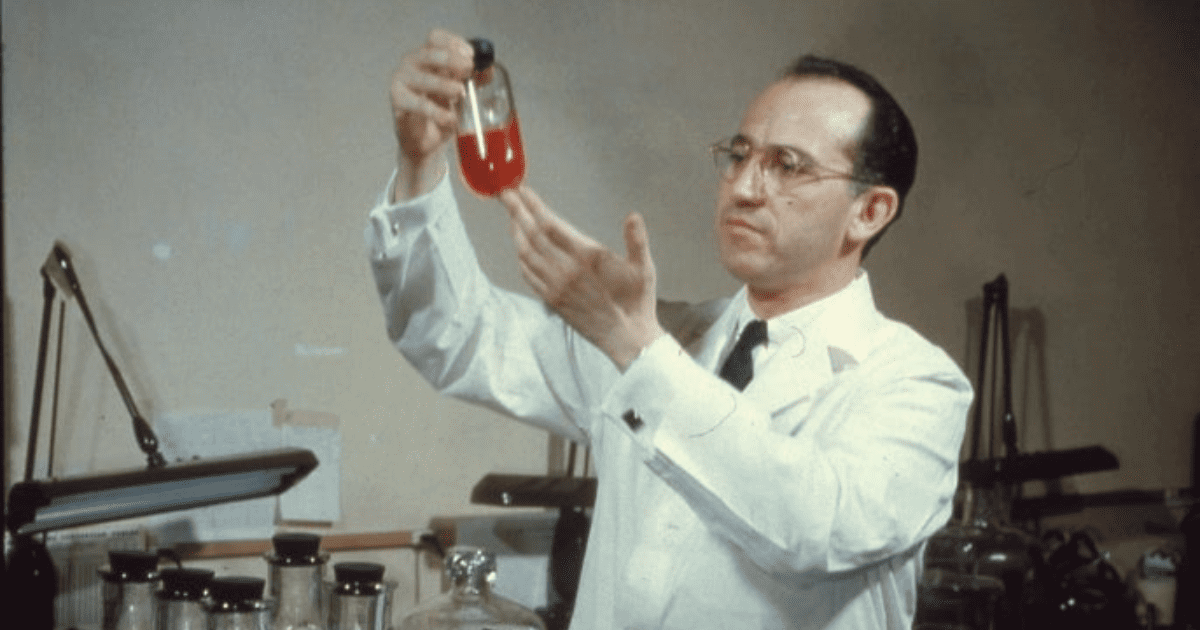

After his monumental triumph over polio, Jonas Salk turned his attention to researching diseases like multiple sclerosis and cancer. He studied how viruses spread and made significant contributions to the field of virology. When asked if he preferred to live enjoying fame or working quietly, the scientist confidently chose the latter.

From the mid-1980s, Jonas Salk worked on an AIDS vaccine, considering it his life’s work. By 1995, the Food and Drug Administration had approved studies of his “Remune” drug, based on parts of a killed virus. These studies were conducted after his death.

In addition, the scientific institute led by Salk was developing a vaccine for oncological diseases. The virologist was confident in the success of this project but did not live to complete it. Work in this area continues today. The institute, located in California, was named in his honor. A prestigious award, established by the March of Dimes Foundation for outstanding virology researchers, also bears his name.

Jonas Salk passed away on June 23, 1995, at the age of 80, from heart failure. Four days before his death, the virologist wrote in his notebook about how one could use their skills, or allow others to use them, to further improve human life. This was the main goal of his life, and one he successfully achieved.