In the 19th century, New York City was hit by several cholera outbreaks. Three of them, in 1832, 1849, and 1866, were particularly devastating and destructive for the city’s working-class neighborhoods, which were overcrowded and had poor sanitary conditions. The first epidemic killed about 3,500 people, and the ones that followed were even deadlier. Have a closer look at those times and their consequences on i-new-york.

The Cholera Epidemics in New York City: Background

The 19th century saw New York City grow at an incredible rate. Thousands of people flocked to the city of opportunities from all over the U.S. and other countries. However, this rapid population growth became a source of many problems, including widespread disease.

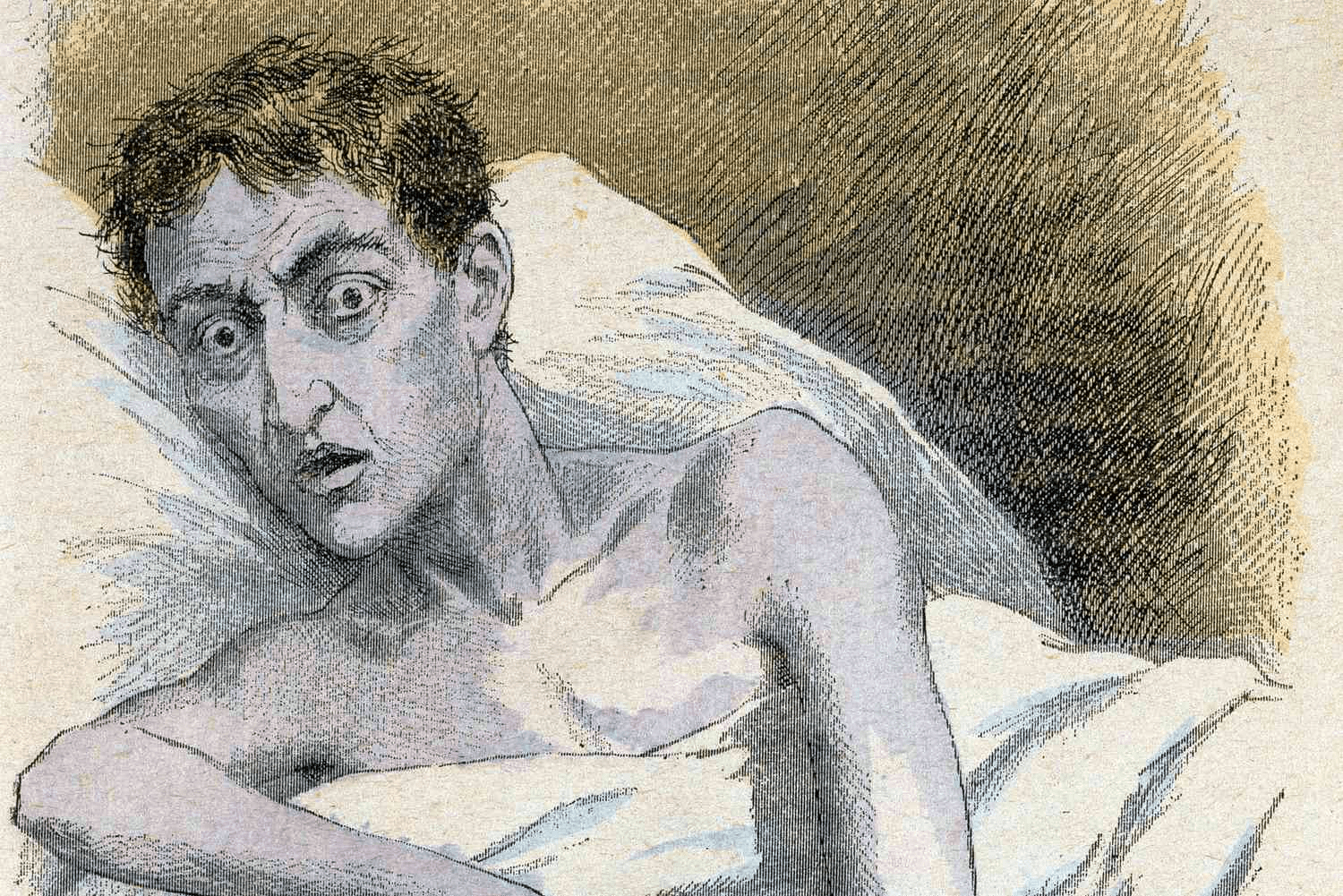

Cholera, a dangerous disease, began spreading from India in the early 19th century. Sailors traveling the world first carried it to Europe. In 1831, the new, frightening disease struck England. A year later, cases were being reported in Canada and on Manhattan, where a real epidemic began.

Wealthy New Yorkers were aware that cholera was coming. Many of them moved to the countryside. However, poor people did not have that option. All they could do was wait for the disease and inevitably face it. The city’s first major cholera epidemic began in June 1832 and peaked in the following months. Manhattan’s working-class neighborhoods were hit the hardest.

The 1832 Outbreak

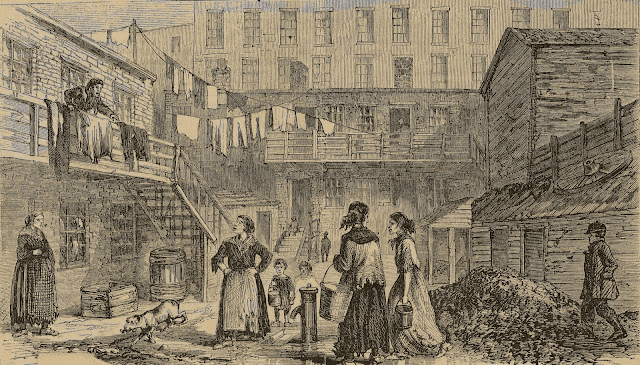

In 1832, New York had 15 separate wards. The city was home to about 250,000 people, most of whom lived below 14th Street in terrible sanitary conditions. The first neighborhood to report cases of cholera was what was then called Five Points. It was home to poor Irish immigrants and African Americans. Since no one at the time knew the real cause of the disease, cholera was thought to be God’s punishment for the sins of the poor.

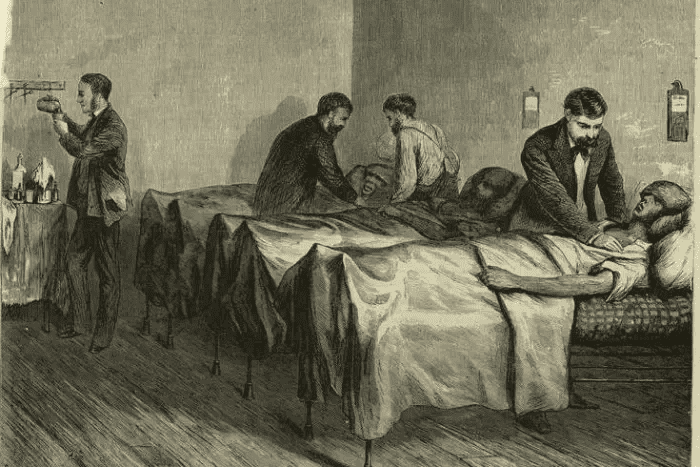

Doctors didn’t know how to deal with the new disease. It was believed that cholera was spread by poisonous vapors and was not contagious. Patients were mainly treated with traditional methods—namely, bloodletting, calomel (mercurous chloride), and the opiate laudanum. Most of the infected people died almost immediately after being admitted to hospitals. In doing so, they infected doctors and nurses.

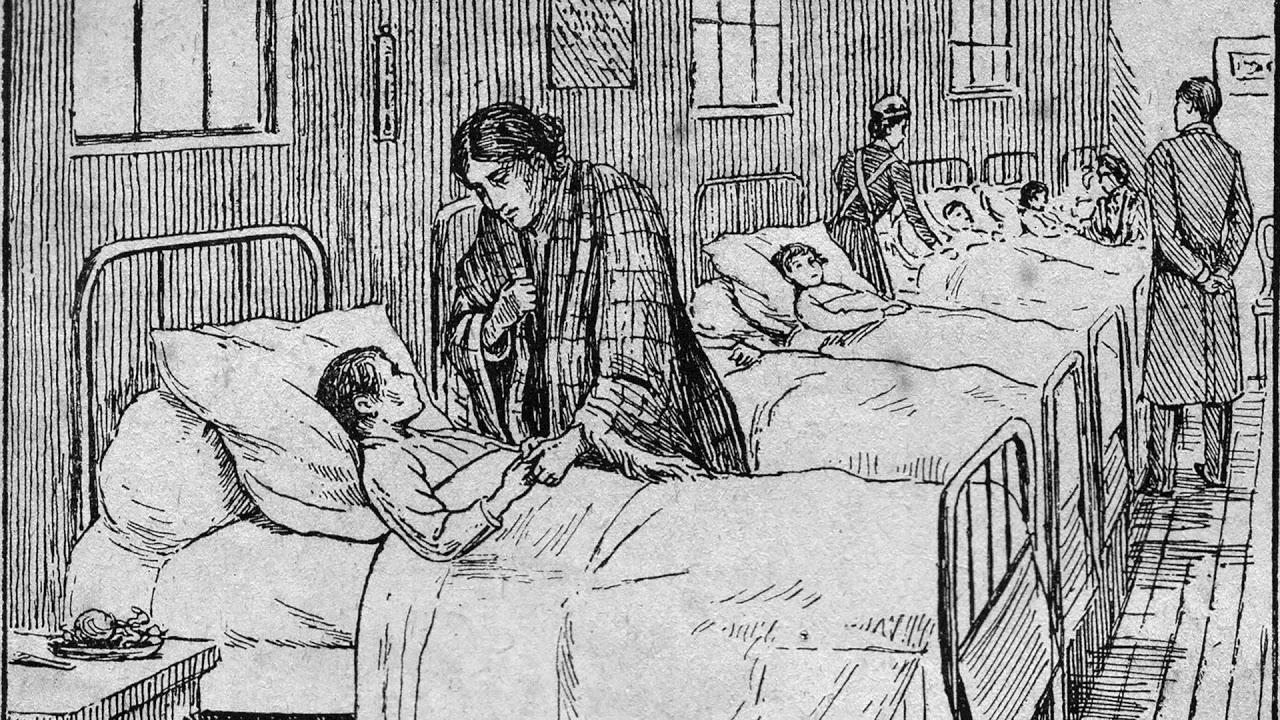

Panic began in the city. Private hospitals closed. The city government decided to open emergency rooms in schools. The Board of Health, which had been operating in New York since 1805, had virtually no authority or resources to effectively combat the epidemic. However, it managed to open five emergency hospitals and start cleaning the streets. The epidemic gradually faded away, but no lessons were learned.

Cholera in 1849

Over the next 17 years, New York’s population roughly doubled. People lived in densely packed apartment buildings and boarding houses for the poor. There was even more dirt and waste on the streets, but no one was concerned with creating a sanitation system.

During this period, a new cholera outbreak emerged in Europe, and in 1849, sailors brought the disease back to the U.S. One of the merchant ships was quarantined on Staten Island, but some passengers escaped. That’s how cholera started spreading in New York again. In early spring of 1849, it became clear that a new epidemic had begun, and by the end of the year, more than 5,000 people had died.

Doctors were once again unprepared to fight cholera. Not all states required them to be licensed, which led to improper record-keeping and a lack of necessary knowledge and experience. The Board of Health set up several hospitals for the sick in schools, but its authority ended there.

The city’s residents were virtually abandoned by the authorities. No one still knew the real causes or treatments for cholera. Therefore, unfortunately, most of the infected died, and no one could do anything about it.

Measures to Prevent the Epidemic

The second cholera epidemic to strike New York was a turning point in preparing for new outbreaks. It was known that the disease would appear in Europe from time to time, so its spread to the U.S. was only a matter of time.

In 1864, wealthy residents of the city came together and created the Council of Hygiene and Public Health. They conducted a survey of living conditions in Manhattan and described the unsanitary situation in detail. The more than 300-page document was published in 1865 and became the basis for public support for a renewed Board of Health and proper funding for it.

Without waiting for a new epidemic to begin, the Board of Health issued orders to clean up the city, especially places where waste was stored. Its representatives pressured local leaders to improve the sanitary conditions of their neighborhoods. Some business representatives refused to cooperate, but gradually, Manhattan became cleaner. This had a positive impact during the last cholera outbreak recorded in the city in 1866.

The 1866 Cholera Epidemic

When the first ship with registered cases of cholera on board arrived in New York, it was quarantined in an uninhabited area. Despite all efforts, the disease still began to spread through the city. However, it was much slower than usual. The poorest neighborhoods of New York were mostly affected, but the mortality rate was low.

At the time, the total population of the city had already exceeded 1 million people, so the measures taken earlier really worked. In addition, the renewed Board of Health did a lot to limit the spread of the disease throughout the city. Small rescue teams were trained, an emergency hospital was established, and a plan for disinfecting the city was developed.

Dr. John Snow’s discovery about the nature of cholera played an important role in curbing the epidemic. He established that this dangerous disease is spread through water. This allowed the city government and residents to take an active role in the fight against and prevention of cholera in New York. The disease was no longer scary or perceived as God’s punishment. Instead, it became clear how to treat and prevent it.

Despite the pain of loss and the panic that enveloped the city each time cholera spread, these three epidemics provided important lessons and knowledge that contributed to the development of New York City:

- The three cholera outbreaks highlighted the striking inequality in the city, where the main burden of the disease fell on the poor and marginalized populations, especially immigrants and African Americans.

- The epidemics led to increased awareness of sanitation and public health and eventually resulted in a significant improvement in the condition of New York for all its residents.

- Cholera led to the development of various public health initiatives, one of which was the construction of the Croton Aqueduct, which improved access to clean water for many citizens.

- The renewal of the Board of Health was also an important milestone in the development and history of the city.

All of this together became a strong foundation for creating higher standards of living for future generations and set priorities for fighting future epidemics. New York and its residents learned the lessons that the cholera epidemics brought with them. Since then, the disease has not returned to the city in the form of large and dangerous outbreaks.