The name Gertrude Elion is well-known in scientific circles. She was a chemist, pharmacologist, and a person who loved exploring the unknown. From the first antivirals and AIDS medications to drugs that made organ transplants possible and treatments for cancer—the list of her achievements is vast. Thanks to her resilience and curiosity, the world took a major leap forward in the fight against many diseases. Gertrude also serves as an inspiration for anyone pursuing a dream. Doors were slammed in her face and she faced rampant gender discrimination; she spent years searching for work while relentlessly studying the unknown. Despite everything, Gertrude Elion never gave up and earned the highest rewards: healthy patients and a Nobel Prize. Read more at i-new-york.

The Path to a Dream

Gertrude Elion was born, raised, worked, and lived in New York. Her family was of Jewish descent, and her parents moved to the U.S. as teenagers. In the metropolis, her mother and father found success and provided a dignified life for their children. Gertrude’s father worked as a dentist, and the family’s spacious apartment was adjacent to his office. Her mother, an exceptionally intelligent woman who cared for the children, was Gertrude’s primary inspiration. Elion often emphasized that although her mother lacked a university degree, she possessed immense wisdom. Gertrude inherited the best traits from her family: a thirst for knowledge, perseverance, and self-belief. From a young age, the future chemist was interested in everything at once, making her career path hard to predict. She was fascinated by history, acting, languages, and science. Remarkably, she excelled in all of them. However, her carefree life ended quite early.

First, the family lost their fortune in the 1929 Wall Street crash, followed by a move and then a tragedy that deeply affected her. Although the family had to change their lifestyle and move to a smaller home, Gertrude remembered that period fondly. It was when her younger brother was born, and the children had a happy childhood. Elion was a true prodigy, graduating from high school at 15. Yet, at that same age, she lost one of the most important people in her life—her grandfather—to stomach cancer. This event impacted her so deeply that there was no doubt about her future profession. Gertrude wanted to end the suffering of the sick and find a cure for cancer. Since she had a sensitive heart and could not bear the thought of dissecting animals, she chose chemistry as her weapon.

The future scientist entered Hunter College and became a certified chemist by 19. Gertrude excelled at the college and graduated with honors. However, her academic achievements initially meant little in the real world. Due to a lack of funds, she had to postpone further studies and look for work. No prestigious positions were available to her, as scientific research was considered a man’s job at the time. Consequently, Gertrude had to accept any available opportunity.

She taught chemistry and worked as a lab assistant, often performing tasks for free and enduring ridicule, just to eventually study at New York University. During this time, she faced another painful loss: in 1941, her boyfriend died from acute bacterial endocarditis. Gertrude felt she had no right to give up; she still had a goal—to help humanity by inventing medicines. When Elion earned her master’s degree, World War II had begun, and women finally got their chance to work. Gertrude seized the opportunity. She worked at Quaker Maid and Johnson & Johnson, but testing food freshness didn’t interest her much, and the lab soon closed. However, when one door closes, another opens.

A Scientific Duo

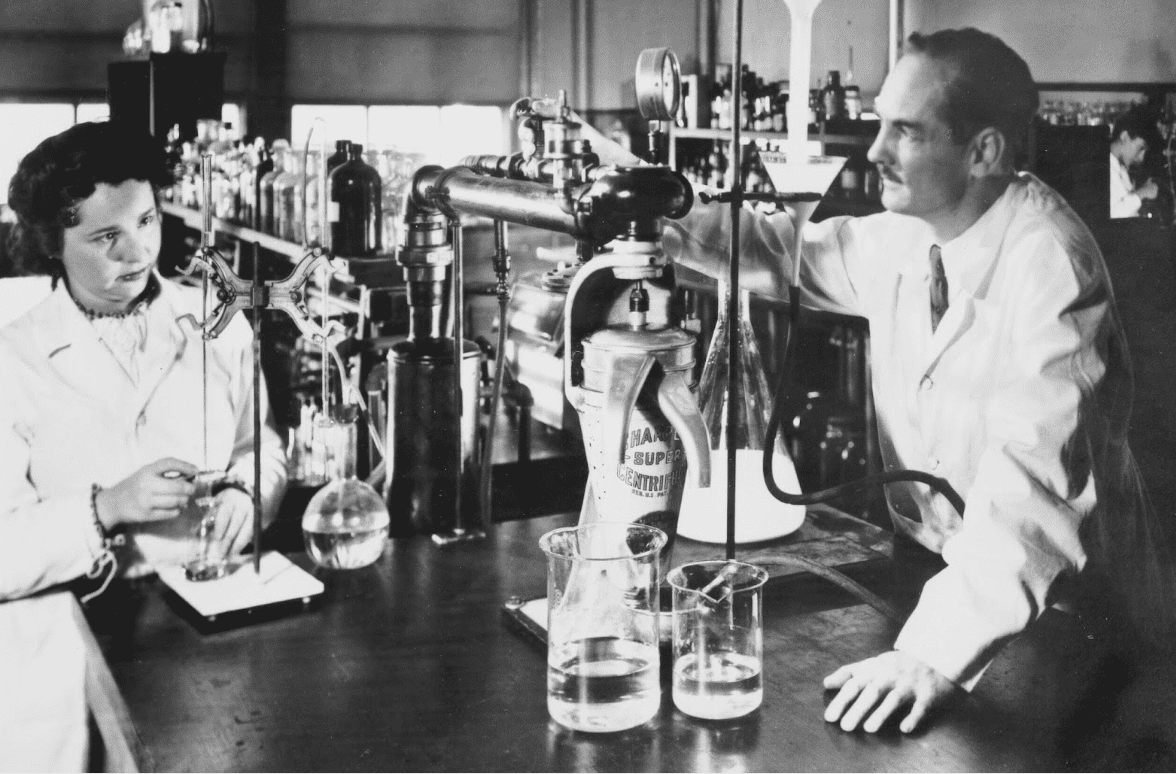

The turning point for Gertrude Elion was joining the pharmaceutical company Burroughs Wellcome. In 1944, she was unemployed but not without offers. Her reputation had grown, and employers noticed her talent. Among many options, she chose a position at the Burroughs Wellcome laboratory. The chemist followed her father’s advice and was not mistaken. George Hitchings became her mentor, colleague, and partner. While their connection wasn’t immediately obvious, they formed a legendary scientific duo.

Their first meeting was marked by skepticism. Hitchings became her supervisor and, in some ways, a rival. One lab employee even suggested not hiring Elion because she was “too well-dressed.” However, Hitchings immediately recognized her potential and offered her $50 a week, believing she would be a valuable asset. He was right. Although the laboratory was small and scientists had to run between floors and offices, it was a dream job for Gertrude. Here, she was supported and inspired, given freedom and encouraged to experiment. While at Burroughs Wellcome, Elion also pursued a doctorate at Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute. When she was eventually pressured to choose between her job and her degree, George Hitchings convinced her to stay. Thus, Gertrude gave up her PhD but achieved something far greater.

Hitchings and Elion were seen as either madmen or geniuses because they revolutionized drug development. They abandoned “blind” trial-and-error searching in favor of a research-based approach. Hitchings assigned Gertrude to work on purines, which are components of DNA. They planned to create copies of these compounds that malignant cells would mistake for the originals but could not use to replicate. This became the basis for 6-MP, which Gertrude presented in 1951. Despite many failures and frustrations, children finally received a treatment for leukemia. Their next achievements were pyrimethamine for malaria and toxoplasmosis, and trimethoprim for urinary tract infections. Furthermore, Gertrude published numerous articles, and much of her work laid the foundation for other scientists’ breakthroughs.

Gertrude’s Medicine

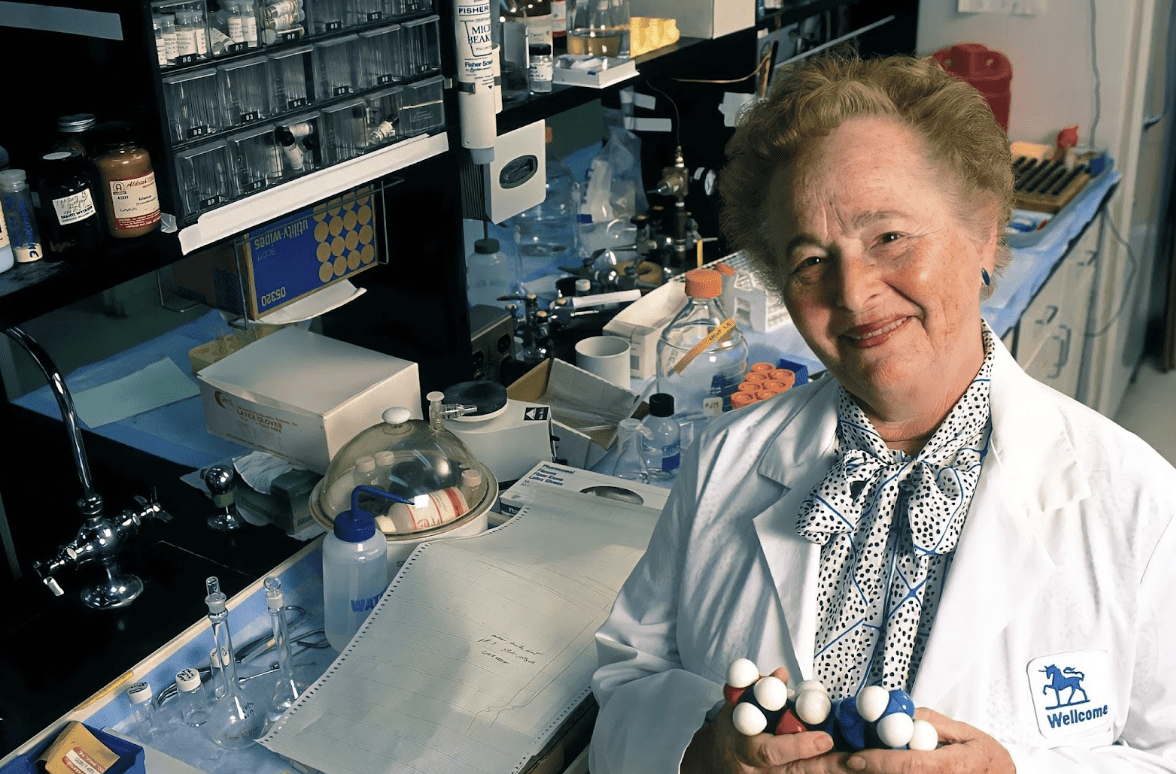

As long as George Hitchings was at Burroughs Wellcome, Gertrude remained under his mentorship. Despite their joint successes, many colleagues doubted her individual contribution. In 1967, she finally had the chance to prove her worth once again. That year, her mentor retired, and Elion was appointed Head of the Department of Experimental Therapy. She faced a massive workload—immunology, virology, pharmacology, and more. But she was undeterred, diligently working on her brilliant discoveries in the lab.

Her skilled hands and brilliant mind led to the invention of allopurinol, which relieved chemotherapy symptoms and treated gout. Azathioprine, which made organ transplants possible, caused an even greater stir. However, she considered her last and perhaps most important achievement to be the creation of acyclovir—the first antiviral drug. Elion sparked a revolution by taking on a task everyone else thought was hopeless. Scientists at the time believed that any substance capable of fighting viruses would be too toxic for humans. Many of Gertrude’s colleagues had long accepted that viral diseases would remain incurable. But while others weren’t even asking the question, Elion already had the answer. She had suspected a possible cure as early as 1948. She had the patience and strength to see it through and, in 1978, presented the world with a solution to many problems.

Gertrude Elion was wrong about one thing. She called acyclovir her “last pearl” too soon. Although she retired in 1983, she couldn’t leave her work behind. She continued to mentor other scientists and left behind invaluable research. Her studies led to the discovery of another drug—AZT, used to treat AIDS. Though she modestly downplayed her contributions, they were vital to science. In 1988, she was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine alongside George Hitchings and James Black.

Life Beyond the Lab

Everyone knew Gertrude Elion not only as an outstanding researcher but also as a fascinating person. From childhood, she possessed a thirst for knowledge that never seemed to leave her. Though she endured many tragic episodes, they never shook her confidence in the future. When the young chemist searched for her first job and was rejected everywhere, she couldn’t understand it. Her family had given her absolute self-belief and determination. Elion could not even fathom facing discrimination. Nevertheless, she moved through life with ease and composure. Many attempts eventually led her to her life’s work.

Colleagues and friends noted her deep empathy. She could not forgive herself for any failure that led to a patient’s death. This drove her to give her all to finding effective treatments for cancer, viral infections, and other diseases. While Gertrude loved her time in the lab, she also enjoyed life outside of it. She spent most of her life in New York, playing on playgrounds first with her brother and later with his children. She loved her nieces and nephews like her own and spent all her free time with family. Elion also adored traveling, something she couldn’t do much in childhood. It is hard to find a corner of the planet she didn’t visit as an adult. She also loved attending the Metropolitan Opera, was fascinated by ballet, and enjoyed listening to music and reading poetry. She considered her work the most interesting in the world—a passion she passed on to her many students and protégés.