To some, he was a hero of American capitalism who fostered the modernization of transport and the creation of a national market. To others, he was a robber baron and a ruthless entrepreneur who mercilessly eliminated competitors. But without a doubt, Cornelius Vanderbilt became a symbol of the era of industrial titans—a time when New York grew from a trading center into the financial capital of the world. Read on i-new-york.com for more about his life and career path.

The Boy on a Boat Who Changed America

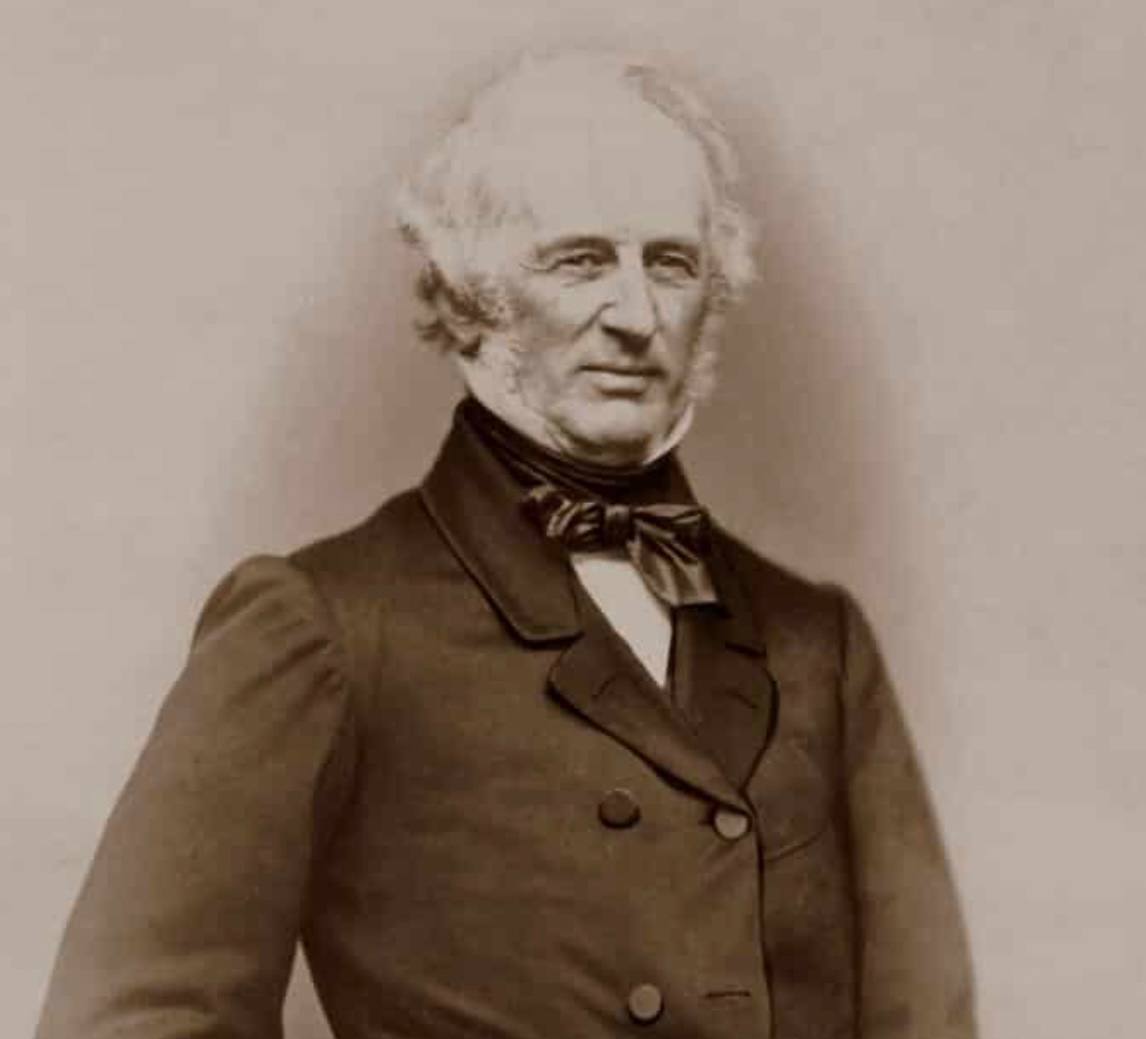

Cornelius Vanderbilt was born on May 27, 1794, on Staten Island, into a family of common people. His father, a ferryman and farmer, sailed produce between Staten Island and Manhattan, and his mother was known for her thrift and strong character—traits that her son later inherited.

Cornelius grew up near the harbor, where the sound of wind in the sails and the cries of gulls were part of daily life. He didn’t attend school for long; by the age of eleven, the boy was helping his father transport goods. However, an entrepreneurial spark flickered within him from a young age. At sixteen, Vanderbilt decided to start his own ferry business. He borrowed one hundred dollars from his mother, a huge sum for the time, and bought a small two-masted sailboat called Swiftsure.

His business was simple but boldly organized—transporting passengers and goods between Staten Island and New York at lower prices than his competitors. The young boat owner quickly attracted attention with his energy, directness, and zeal. Peers at the harbor began jokingly calling him “The Commodore”—a nickname that became his second name for life.

In 1813, nineteen-year-old Cornelius married his cousin, Sophia Johnson. It was then that fate brought Vanderbilt together with entrepreneur Thomas Gibbons, who offered him the position of steamboat captain on the line between New York and New Jersey. Working with Gibbons became a school of big business for Cornelius. He learned to manage not only ships but also people, finances, and legal disputes.

At the time, no one suspected that the young ferryman with Dutch roots would soon transform into one of America’s most influential businessmen—a man who would build a transportation empire, change the face of the country, and go down in history as the legendary “Commodore” Vanderbilt.

From Riverboats to Ocean Liners: A Steamboat History

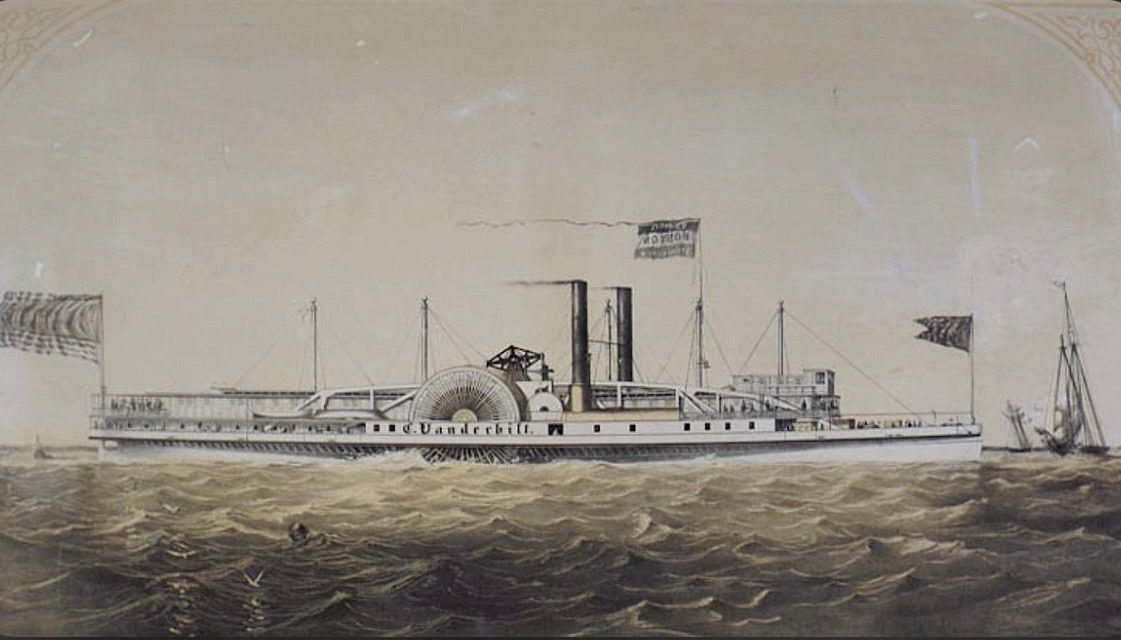

After Thomas Gibbons’s death, young Cornelius worked for Gibbons’s son for a few more years but quickly matured into his own business. In 1829, he started his own steamboat company, which eventually covered routes from New York to surrounding cities. His entrepreneurial spirit led to fierce competition—first with Daniel Drew, with whom he secretly partnered after a struggle to avoid price wars.

In the 1830s, Vanderbilt challenged the monopoly on the Hudson River by creating the “People’s Line.” His cheap tickets and slogans about “people’s power” quickly gained popularity, and eventually, the monopolists were forced to pay the ambitious “Commodore” for peace.

Over the next decade, Cornelius built his fleet, bought up real estate and transportation companies, gradually becoming the master of the East Coast. The biggest success of the 1840s was the “New York—Providence—Boston” line.

The California Gold Rush opened up ocean horizons for Vanderbilt. His company provided the fastest route to the Pacific via Nicaragua and brought millions in profit. But eventually, his partners betrayed him. Cornelius responded in his own style—he launched a new line, crashed prices, and forced his rivals to buy peace again.

He also conquered the Atlantic, creating his own transatlantic company, buying up shipyards and ironworks, and becoming the owner of Allaire Iron Works.

Even when Vanderbilt lost his Nicaraguan assets in the 1850s to the adventurer William Walker, he did not retreat—he backed a military expedition that overthrew the usurper and regained control over shipping.

By the end of the 1850s, “The Commodore” already owned a fleet, real estate, shipyards, and millions of dollars in capital. His name became synonymous with success, power, and ironclad business acumen. But the most grandiose victories were yet to come—on the rails of American railroads.

The Birth of the Railroad Empire

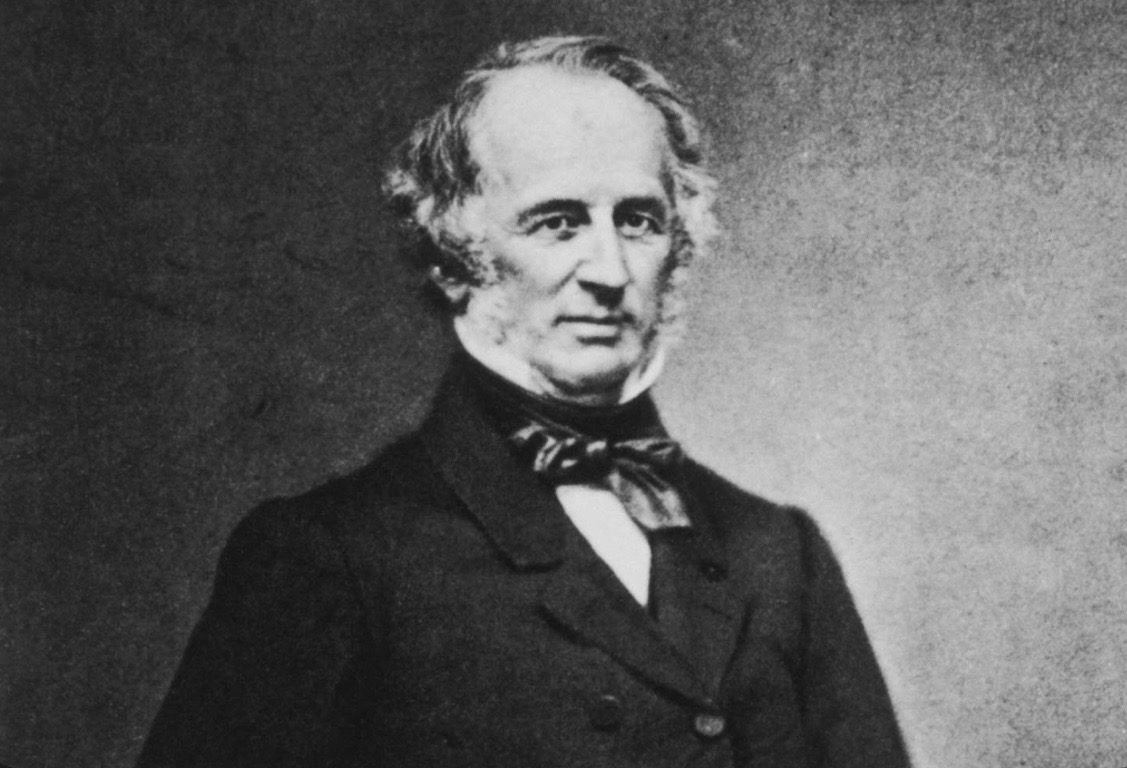

When Cornelius Vanderbilt realized in the 1860s that the future of transportation lay not with steamboats but with railroads, he changed course without hesitation. By that time, he was already seventy years old and could have quietly enjoyed his accumulated wealth. But instead of retirement, “The Commodore” began a new game—bigger, riskier, and more massive than ever.

In 1863, Vanderbilt acquired a controlling interest in the New York and Harlem Railroad—a company Wall Street considered hopeless, but which held a key advantage. It was the only steam railroad that ran through the center of Manhattan, along Fourth Avenue (now Park Avenue) and reached a station at 26th Street.

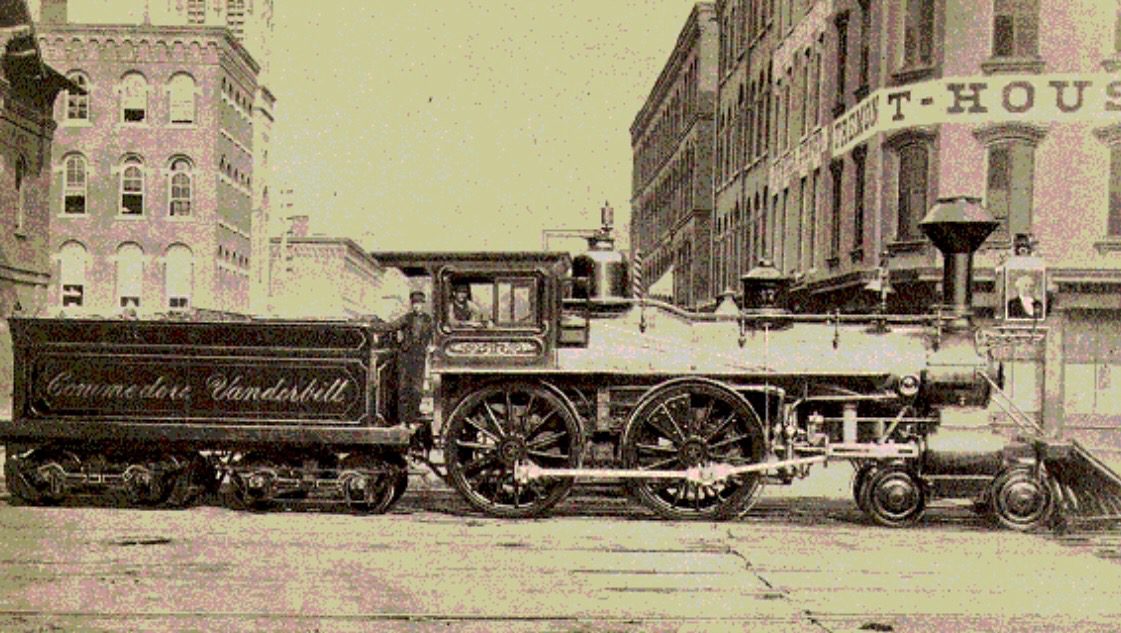

Vanderbilt brought his eldest son, William Henry, into the management. In 1864, Cornelius sold his last ships, finally saying goodbye to the maritime era of his life. After gaining control of the Harlem line, he entered a series of fierce battles for other railroads. In 1864, Vanderbilt acquired the Hudson River Railroad; in 1867, the New York Central Railroad; and two years later, the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern, which connected Cleveland and Chicago. He also added Southern Canada to his holdings.

In 1870, “The Commodore” consolidated all these assets into a new corporation—the New York Central & Hudson River Railroad—one of the first giant transportation companies in America. It was the first railroad to provide continuous service between New York and Chicago—a true artery connecting the East and West of the country.

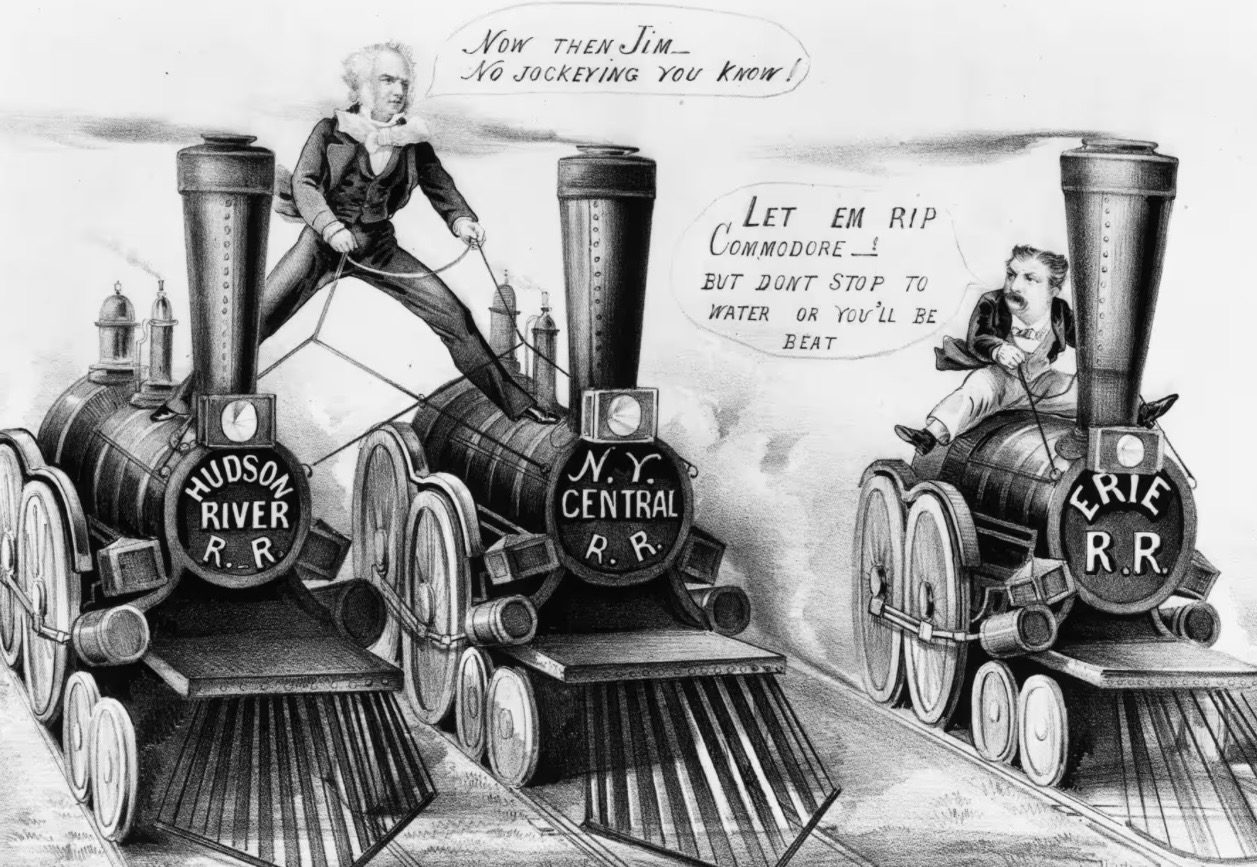

To underscore the grandeur of his new empire, Vanderbilt decided to build a monumental terminal in the heart of Manhattan. In 1871, the magnificent structure opened its doors to passengers. It featured a glass roof, elevated platforms, and comfortable waiting rooms—innovative elements for its time. In 1868, Vanderbilt engaged in a high-profile financial war—the struggle for control of the Erie Railroad. His rivals included legendary speculators Jay Gould, James Fisk, and former ally Daniel Drew.

“The Commodore” tried to corner the company’s stock, buying them up to seize control, but Gould and Fisk began printing “watered” securities en masse—essentially fake ones, but legalized through bribes in the state legislature. The press dubbed this confrontation the “Erie War,” and Vanderbilt, “the toughest of the robber barons.”

But despite his financial losses, Cornelius managed to recover some damages and maintained his influence. Gould never defeated him in any major deal again, although he remained a constant irritant. By the end of his life, Vanderbilt owned a railroad system stretching from the Atlantic to the Great Lakes. He not only made the railroads profitable but also standardized schedules, improved service, and introduced new management principles.

The Final Years and Legacy of Cornelius Vanderbilt

In 1876, “The Commodore’s” health deteriorated sharply. For eight months, he was confined to bed in his home on Washington Place in New York. On January 4, 1877, at the age of 82, Cornelius Vanderbilt died of exhaustion caused by prolonged gastrointestinal illness.

At the time of his death, his fortune was estimated at $105 million (the equivalent of over $3 billion in modern money)—an unprecedented sum for the era.

In his will, he left 95% of his entire estate to his favorite son, William Henry, who had helped him manage the railroad empire. The rest of his children (nine daughters and one son) received relatively small inheritances. The offended heirs contested the will, claiming that their father was elderly and under the influence of William and even spiritualists who allegedly advised him that this son should inherit the business. The legal battle lasted over a year and ended in a settlement. William paid his sisters and brother several hundred thousand dollars each.

Despite the fact that Vanderbilt was not a generous philanthropist during his lifetime, his activities changed the U.S. economic landscape. As biographer T.J. Stiles wrote:

“He helped transform the nation’s transportation infrastructure and laid the groundwork for the corporate economy that would define 21st-century America.”

Cornelius lived relatively modestly, spending his fortune primarily on racehorses and business. However, thanks to his capital and entrepreneurial approach, the Vanderbilt surname became synonymous with luxury, influence, and the American economic miracle.

In 1999, Cornelius Vanderbilt was inducted into the North America Railway Hall of Fame, and his bronze statues stand today near Vanderbilt University in Nashville and Grand Central Terminal in New York—as a symbol of the man who built an incredible empire from a simple ferry landing on Staten Island.